Watch out for Zombie Records! Yours can hurt you.

How Sealed or Expunged Court Records in Tenant & Employment Screening Reports May Illegally Cost People Jobs & Housing

From the National Consumer Law Center, June, 2022

Today, to rent an apartment or nail down a job, you almost always have to pass a background check.

About 94% of employers and 90% of landlords run criminal background checks, and about 85% of landlords review eviction information. Many landlords and employers purchase reports containing criminal and eviction records information from specialized tenant and employment screening companies, which often scrape information from online court databases or buy the information from a third-party data broker or vendor.

Landlords and employers often turn down applicants with a criminal record. Landlords often also automatically reject applicants with eviction case records, regardless of the context, outcome, or how long ago the case was filed. Background screening therefore wields significant influence over people’s lives and financial circumstances.

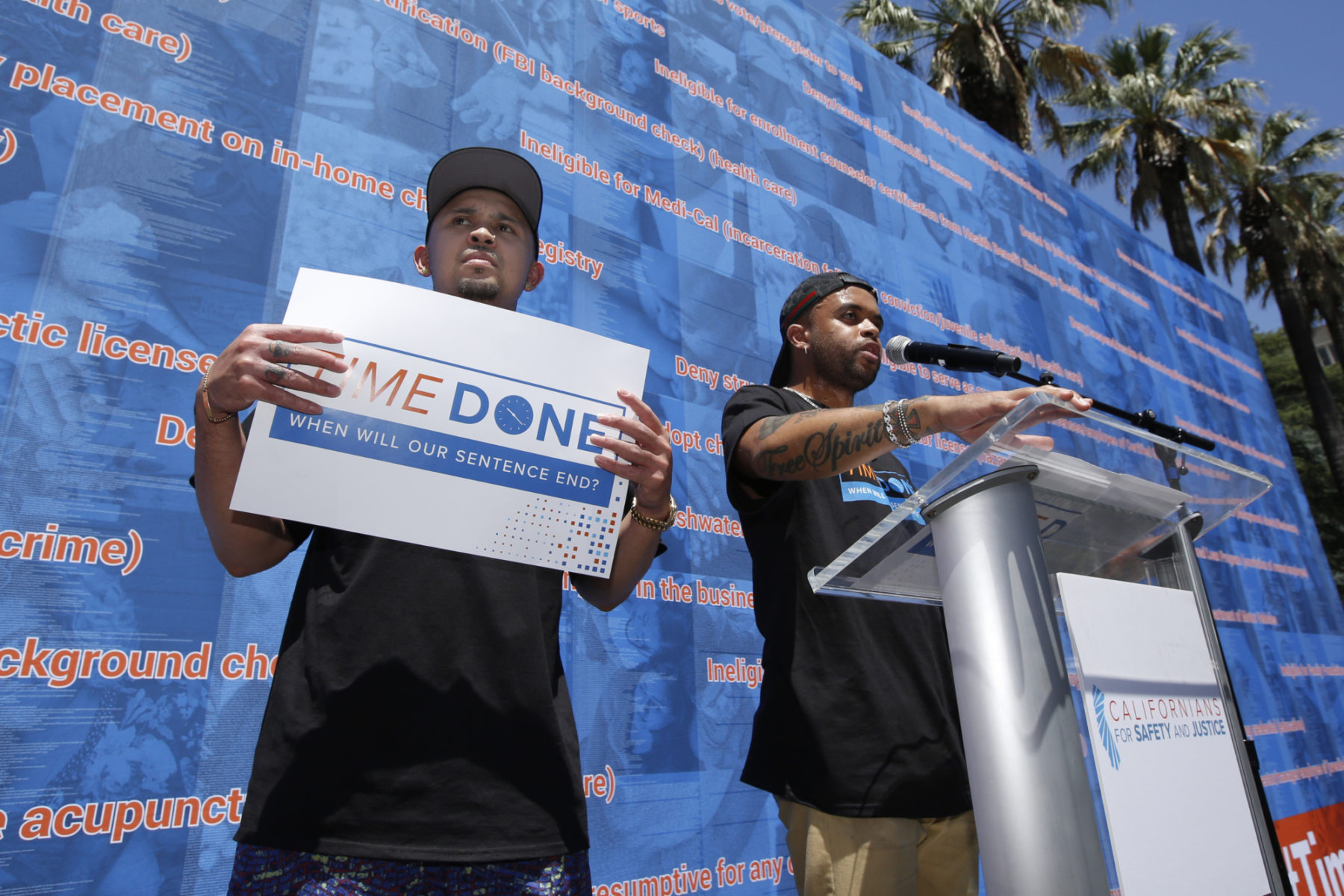

Because people of color—and Black people in particular—are more likely to have a criminal record, largely due to the racial bias that infects every stage of the criminal legal system, the negative consequences of criminal records disproportionately harm these communities.

Black and Latinx renters—and women in particular—also face a disproportionately high risk of eviction.

What are “expunged” and “sealed” records?

“Expunged” and “sealed” have different meanings in different states. In some states, expungement means that the record is eliminated or destroyed, and sealing means that the record is unavailable to the public. In general, state laws that allow for expungement and sealing are intended to stop landlords, employers, and others from viewing records. They also can prevent commercial screening companies from collecting and reporting these records on tenant and employment screening reports.

Record-Clearing Laws Can Reduce the Long-Term Harms That Flow from Having a Criminal or Eviction Record—As Long as Screening Companies Follow the Law

Recognizing that lingering criminal records are a barrier to housing, jobs, and economic stability and often are not useful predictors of someone’s ability to be a successful tenant or employee, states around the country have adopted record-clearing laws as a way to give people a fresh start.

Forty-five states now allow people to expunge, seal, or set aside certain convictions in some circumstances, and nearly all states authorize sealing of certain non-conviction records. Read what Kansas does to restore people's rights.

Similarly, a growing number of states have passed eviction- sealing laws. Some states have enacted these laws specifically to help their residents secure future housing and recover from the COVID-19 economic crisis.

Screening companies completely undermine these state laws when they report people’s sealed or expunged criminal or eviction records.

When screening companies or their vendors fail to regularly update their data, they will often improperly include sealed or expunged records in reports to prospective landlords, employers, and others. The impermissible reporting of these records costs people housing and jobs and harms their reputations. It also harms businesses and housing providers by leading them to make incorrect decisions about applicants.

Helen Stokes had two arrests stemming from domestic disputes with her then-husband, which were dismissed and expunged.

When Ms. Stokes was 63 years old, two senior living centers denied her application for a residential lease when a tenant screening company wrongfully reported the expunged arrests. The screening company reported the expunged criminal charges even though more than six months had passed since the cases had been eliminated from all public records.

Ensuring that screening companies properly exclude sealed or expunged court records will help reduce barriers to jobs and housing. As people try to recover from the COVID-19 economic crisis, it is more critical than ever that screening companies get it right. When screening companies get it wrong, they not only undercut states’ efforts to give their residents the opportunity to move forward with their lives, but they also risk violating the federal Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA).

The FCRA requires all consumer reporting agencies (CRAs), including tenant and employment screening companies, to “follow reasonable procedures to assure maximum possible accuracy of the information” they report (15 U.S.C. § 1681e(b)). Employment screening companies also must “maintain strict procedures designed to insure that whenever public record information which is likely to have an adverse effect on a consumer’s ability to obtain employment is reported it is complete and up to date” (15 U.S.C. § 1681k). Reporting records that have been expunged or sealed does not “assure maximum possible accuracy” of reported information nor that the information is “complete and up to date,” and may violate Sections 1681e(b) and 1681k.

Trevon L. Estes was denied housing twice because a tenant screening company reported an eviction record that had been expunged. After Mr. Estes made his monthly rental payment, his housing provider’s offices were burglarized, and Mr. Estes’ payment was stolen. The housing provider filed an eviction action against him for unpaid rent.

Eventually realizing and admitting its mistake, the housing provider dismissed the eviction action and asked the court to permanently expunge the record, which the court did. But when Mr. Estes tried to rent a new apartment nearly two years later, the tenant screening company reported his expunged eviction record, and the prospective landlord denied his application.

The same thing happened a second time; Mr. Estes was denied housing again when the same tenant screening company reported the same expunged eviction record.

Recommendations

For the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau:

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau should take action to stop tenant and employment screening companies from denying consumers their chance at fresh start in accessing employment and housing by:

- Issuing guidance stating that reporting public records that are sealed, expunged, or subject to similar relief may contravene section 1681e(b) of the FCRA. The CFPB should make clear that a CRA violates this section of the Act where it fails to follow reasonable procedures to assure that the information contained in its screening reports reflects the current public record status of a consumer’s information and then reports criminal or eviction records that have been sealed, expunged, or subject to similar relief.(1)

- Issuing guidance clarifying that a CRA violates section 1681k of the FCRA if it fails to maintain strict procedures to ensure that the information contained in its employment screening reports is complete and up to date and then reports criminal records that have been sealed, expunged, or subject to similar relief.(2)

- Collaborating with the Federal Trade Commission to investigate and bring enforcement actions against tenant and employment screening companies that report court records that have been sealed, expunged, or subject to similar relief in violation of the FCRA.

For states:

In addition to enacting legislation that allows for sealing or expungement of certain criminal and eviction records, states should take action to ensure that any records that have been sealed or expunged do not continue to harm consumers. In particular, states should:

- Promptly remove from all public records databases any court records that have been sealed, expunged, or subject to similar relief.

- Require companies that purchase or otherwise obtain court records information electronically to have procedures for ensuring that sealed and expunged records are promptly deleted from their files and databases, and require these companies to ensure that their customers and other third-party recipients also properly delete records.(3)

- Regularly audit companies that purchase or otherwise obtain court records information electronically to ensure that they are promptly removing sealed and expunged records, and impose consequences—such as the revocation of the privilege to subscribe to records information in bulk—on companies that fail such audits.(4)

- Prohibit employers and housing providers from reviewing, using, considering or asking questions about court records that have been sealed, expunged, or subject to similar relief when deciding whether to hire a prospective employee or rent to a prospective tenant.

- Through their attorneys general, which have enforcement authority under the FCRA, investigate and bring enforcement actions against tenant and employment screening companies that report court records that have been sealed, expunged, or subject to similar relief.

For more information, contact Ariel Nelson, National Consumer Law Center Attorney (anelson@nclc.org), and Caroline Cohn, Equal Justice Works Fellow sponsored by Nike, Inc. (ccohn@nclc.org).

Read about reinstating suspended driver's licenses in Kansas and other driver's license issues.

Endnotes

1 Such guidance would be consistent with the position both the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) and the Federal Trade Commission have taken in previous enforcement actions. See Consent Order at 5–7, Gen. Info. Servs., Inc., 2015-CFPB-0028 (2015); Complaint ¶ 13, U.S. v. HireRight Solutions, Inc., 12-cv-01313 (D.D.C. Aug. 8, 2012).

2 Such guidance would be consistent with the CFPB’s position in previous enforcement actions. See Gen. Info. Servs., Inc., supra note 1, at 7–8.

3 For more context about how this recommendation has been implemented in court systems that permit companies to buy or subscribe to court records information in bulk, see Consumer Fin. Prot. Bureau, Market Snapshot: Background Screening Reports 16 (2019); Ariel Nelson, National Consumer Law Center, Broken Records Redux: How Errors by Criminal Background Check Companies Continue to Harm Consumers Seeking Jobs and Housing 23, 39 (2019).

4 See Consumer Fin. Prot. Bureau, supra note 3, at 16; Nelson, supra note 3, at 39.